Table of Contents

- 1

- 2 What is the optimal frequency for the 3 main lifts, particularly the squat?

- 3 How, as an athlete without a coach, can I stop technical breakdown at weights ~90%?

- 4 Should the goal in meets be to always go 9/9?

- 5 What are the physiological aspects for the lifter and coach when competing?

- 6 What does it mean to be a coach, technically and psychologically?

- 7 All else held equal, how does online coaching compare to in-person coaching (including when it comes to custom vs. general programs written by the coach)?

- 8 Why do Russian lifters 3rd attempts look ‘cleaner’ than others?

- 9 What would you recommend to develop technique for an already experienced lifter?

- 10 How long would it take for an ‘inherited’ athlete to gain technical excellence?

- 11 What are the general rules for technique on the big 3?

- 12 What are some general programming rules you follow for the squat?

- 13 How should you train the squat, bench and deadlift differently?

- 14 What do you feel are some things falsely associated with the Sheiko methodology?

- 15 What percentages are generally used outside of a peaking phase?

- 16 Is there a time and a place to fail a lift?

- 17 Getting hyped up for a lift – what is its role in training and competition?

- 18 What defines a novice/intermediate/advanced lifter?

- 19 What are you thoughts on overtraining?

- 20 What do you think of autoregulation (RPE)?

- 21 Closing Comments from Boris Sheiko

On January 18th, 2018, Kizen Training published the most comprehensive translated interview with Boris Sheiko, renowned Russian powerlifting coach.

Clocking in at over at over an hour, the discussion is chock full of great tips and insights from one of powerlifting’s greatest minds.

Lift Vault took a stab at transcribing the Professor Sheiko’s answers and also highlighted what we believed to be the more interesting comments. When you’re done reading, be sure to check out Lift Vault’s Sheiko Program Collection.

Enjoy!

What is the optimal frequency for the 3 main lifts, particularly the squat?

Summary:

- Depends on training age.

- Larger muscles used in the squat and deadlift will take longer to recover than the muscles used in the bench press, so bench is generally programmed more frequently.

- If there are technical problems with a lift, that lift will be programmed more frequently to help fix the technique.

This is a very interesting and deep question. This is highly dependent on training age, with beginner athletes training less frequently as far as overloads are concerned and then at more advanced athletes, being able to train the lift more frequently. Another big factor is the size of the musculature involved in the lift. With pulling and squatting, the muscles of the leg and back are involved, which are very large. And with the upper body, bench press the muscles involved a bit the total volume is much smaller so they don’t require as much time to recover. Another factor is if an athlete has technical problems with lifts, whatever lifts have the most technical problems and thus need for technical corrections are practiced more frequently. It’s actually a bigger problem in advanced athletes who have learned poor techniques because fixing an already poor technical base is much more difficult than building one anew.

It’s a really high priority for a good coach to work on improving an athletes technique when he inherits that athlete from other training histories but one tends to run into a really big problem where the technique could look good up to 80 or 90% of one rep max and then exceeding those loads,basically an automation, a a reflex kicks in and at those loads an athlete reverts back into poor technique. As a coach himself, he pays a lot of attention to making sure that the establishment of technical qualities is exceptional in his athletes so that such mistakes never have to come up.

How, as an athlete without a coach, can I stop technical breakdown at weights ~90%?

Summary:

- If you train without a coach, reaching mastery will take longer

- If you cannot afford a coach or access one, a good, honest training partner is your next best bet

- Other people are useful for making sure your technique is not breaking down at heavier weights

I’m really enjoying talking to you because you are posing very professional and deep questions. First of all, it just inherently, if you’re training without a coach it’s going to be a longer road towards technical perfection and mastery of the lifts, it’s just inherently it’s a trade off you have to make, but if you can’t get access to a trainer, a training partner is at least a very good idea because there’s some stuff you’re just not ever going to be able to accurately see or sense yourself.

A training partner with a bird’s eye view, a third person view, can tell you if you’re hitting depth properly, if everything looks good, if you’re touching your presses to your chest, if you’re locking out properly in a way that you can deceive yourself or just not have access to, but if you have a competent training partner around, that solves some of the problems. If you’re a lifter without a coach you should be watching a lot of videos. There are two kinds of videos: one kind of video is the execution of the lifts at the very highest level by the very best lifters, taking as many lessons as you can from that, but also there are a lot of videos in which people break down the techniques of the lifts point by point that are very educational. You should basically try to consume as much of that content as you can, look into it as much as you can, focus on it a lot, and make sure you’re willingly, actively taking a first person role in making sure you’re on technique. Granted, you should be educating yourself.

If you cannot get a coach, your best recourse is to get a training partner, someone that can be honest with you and someone who can at least be there behind you in a spotting situation, especially the squat or the bench, which can be an extra, an idea that someone is that at very limit weights that can be there just in case so you can express your best technique. A lot of younger lifters are constantly chasing PRs so they don’t learn the technique as well, so when they get to meets they often bomb out or only record one or two recorded good attempts because of technical breakdown and other issues that occur.

Back to Top

Should the goal in meets be to always go 9/9?

Summary:

- An athlete gets a C if they miss an attempt on each lift

- An athlete gets a B if they make all three attempts on at least one lift

- An athlete gets an A if they go 9/9

- You should make as many attempts as possible if you want to win on total

I grade attempts and athletes on an A, B, or C system.

A C performance is an athlete that on every single lift misses at least one attempt.

A B performance is one in which at least one of the lifts he gets all three attempts.

An A performance is one in which an athlete goes 9 for 9.

In addition, when a coach judges other coaches or when he judges athletes from a third person perspective, what he values the most is stability, especially psychologically stability, and dependability and reliability. He would take an athlete whose lifts are 5 kg lower on average but dependently hits his lifts in competition when the goals demand it vs. the athlete that has the potential to hit lifts that are 5 kg more but is not dependable and misses lifts often or bombs out often.

You know, usually when you have World Championship athletes meeting at worlds as the head coach of the Russian national team for a long time, I’ve seen it happen that the most important thing is the guys are just about as strong as each other what really depends at that point in competition is can you reliably hit the attempts you choose.

In 2004 in world champions in Africa student Revil under 60kg competition one of my best of all time was in a meet where he had two really gnarly opponents someone from Indo and one from Taiwan was a real badass as well. I said the champion whose gonna do this is the person that can hit most of their lifts and Sutristno, one of his competitors, actually missed a couple of lifts, but even in spite of that, had managed to increase the current world record at that competition by 7.5kg for a total the Taiwainese at the time world champion who was also in that weight class missed only one lift and with that missed lift he gained 12kg on the world record total at the time and Revil didn’t miss any lifts and he increased the world record by 15kg and he became for the first time in his career a world champion and that would be a tradition that continue would carry for a few years. The fight lasted until the last physical attempt over the pull.

What are the physiological aspects for the lifter and coach when competing?

Summary:

- Yes, psychological strength can absolutely influence the outcome of a meet.

- Between a coach and athlete, the coach needs to earn the trust of the athlete and the athletes needs to trust in the plan laid out by the coach.

One of his lifters Alexs Sivokon he was at the Worlds and he was going up against a gentleman named Austin from the US and he was a 7 times world champion and this is kind of an example I will tell to illustrate the example of psychological stability. So two months before this meet at World’s Sivokon competed in the Asians champions and actually produced a bigger total than Austin had and he was kind of freaking out saying “dude how am I going to compete against this Austin guy?” He’s a 7 times world champ and I said “Look man you already showed a really great result, you hit a bigger PR and he already knows about us so he’s not going to come in as confident as you think.” So he said let’s check this Austin guy’s psychological profile. There was a weigh ins room and there were athletes on both sides in lines waiting to weigh in and I said “go stand in the line opposite to Austin, look him dead in the eyes when you have the chance and see if he lowers his gaze. If he lowers his gaze, we’ve got him.” I said, “So how did it go?” He said “I looked him dead in his eyes and he dropped his gaze.” and I said “Yep, we got ’em” and we won the World championship.

So another alternate example: I had a guy in a Khazikstan meet was doing the numbers that would have got him roughly 3rd place at World championships, when he actually came to compete at the world champions, he weighed 3 kilos less than he was supposed to and he under totaled vs. predicted by 25 kg and took 8th place. I basically said “Hey Andre it’s really hard trying to coach you cause I gotta figure out which weight you’re gonna not bomb out at vs. even trying to go for a world record.” My philosophy for treating world championship athletes that he coaches, I don’t care what place they take, I care about getting the most number of successful attempts as planned and then the chips fall where they may. If they focus too much on getting first, second, third they’ll start losing sleep and changing attempts in their head. This adds a lot of fatigue and really is not worth it at all. Athletes on average tend to over value their strength, especially in high competition, so they think they can lift more than they actually can. The trainer has to be the sober voice and has to be in charge so when his athletes start to ask for more, you say “listen, I’m in charge during the contest. When you get your placing and you start getting the congratulations, you’re in charge of getting them. But for now, let me be the pilot of the ship and let me figure the attempts because that’s our arrangement.”

What does it mean to be a coach, technically and psychologically?

Summary:

- There is no perfect program for everyone, so all programs must be tailored to the individual athlete for a good response to the program.

- A coach must pay attention to the physical and mental health of their athletes and make adjustments to programs as needed.

- It is important to tweak a program based upon the actual performance of the lifter in training, if needed.

- Sheiko gets very frustrated by students that do not follow the program because when an athlete fails a lift, he cannot tell who is messing up: him or the athlete.

First of all, I want to be clear: there is no trainer or coach in the world that can write the ultimate program that makes everyone happy so you need to accept that when you write a program, some athletes are going to respond well to it and some athletes, no matter how good you are, they’re just not going to respond super well to it. But for intermediates and especially advanced people, that’s why individualized programs are really key. I’ve had online athletes that would do the program as written with a fever and I would say “I am not a general and you are not my soldier.” The human being is not a machine where you can set programming instructions and they just do it, do it, do it. My programs are usually a month of a time and I try to predict how bodies will respond and how the athlete will respond, but I can’t do that exactly because outside life stuff happens. We can only approximate and after that, that’s why an individualized program, especially where I’m physically present, sometimes an athlete will start hitting certain lifts and I can see that he’s not ready for some reason or another and we change the plan so that the athlete is not hitting those numbers until they’re ready.

The ultimate sign of a really good trainer or someone who thinks of their athletes and their performance 24/7.

I’ve had situations in the night where I’ll write a training plan late at night, wake up the next morning, read it, and ask “what kind of idiot wrote this?” Having a fresh perspective with rest, I will rewrite the plan to make sure its my best work. A coach has to feel his athletes and get really intimate with understanding their ability to recover so that I am not programming too much. Everything I write personally, I feel through the program, I imagine how my body would respond and how much fatigue I would accumulate and go by there – adjust as needed. I write from experience as well as from technical knowledge. I am very proud that I have never had any athletes over train because I am always very aware of recovery and prioritizes that higher. Champion athletes are built from a fanaticism, an obsession that allows them to give up a lot of other things that they like and make some serious trade offs. To be a great coach you have to do the same. You must be obsessed with ensuring athletes are getting the best quality service. The best situations occur when you have an athlete that wants to be great and a coach that wants to make that athlete as great as possible. If I get pissed at an athlete for not following the program or not being dedicated enough with their extra curricular activities I tell them “you are really frustrating me because when you under perform I can’t tell which one of us is fucking up. Is it me or is it you?”

All else held equal, how does online coaching compare to in-person coaching (including when it comes to custom vs. general programs written by the coach)?

Summary:

- In person coaching is the best

- Online coaching can be good, but the quality can also be very poor. It depends on the person.

- Sheiko has online students and watches their videos weekly in order to provide feedback on technique, weak points, etc.

- If nothing else, an honest training partner can be helpful for feedback and spotting.

So I agree that in person coaching cannot be beat, but the quality of online coaches is a big variable because if you will be a good online coach you can’t just send people programs and forget about them, you have to correspond with your athletes.

I prefer to watch athlete videos – the last two heavy attempts of working sets – I view these once a week to give feedback and tell the athlete what to fix. I get a great degree of pride and effectiveness from watching an athlete over the weeks improve the weak areas that I have pointed out in their program.

In third place is an athlete that trains with a training partner and then dead last place is an athlete that trains without a coach, without a training partner. Such an athlete can get very strong but their technical limitations will be so big that they will consistently lose in competitions against athletes that are actually weaker than them.

Why do Russian lifters 3rd attempts look ‘cleaner’ than others?

Summary:

- Psychologically, American athletes are not any worse than Russian athletes.

- Russian athletes tend to focus more on form from an early age, an emphasis which continues throughout their training career.

- Athletes often have the same coach for a long time, which allows the coach to provide consistent corrective guidance for many years.

First of all, psychologically, I don’t think American athletes are any worse than Russian athletes, but the methodology school is consistently different between Russian and American approaches.

Russia has inherited from the Soviet days an understanding of a system of athlete development from junior level athletes to beginners to junior level athletes to intermediates all the way to masters. Just until recently and as far as currently, most of the coaches that work in Russia work with the youth and development. Something like 80% work with young athletes. So these coaches at these clubs will take athletes in weightlifting from age 10 or so and powerlifting from age 12 or so and they will literally develop through a system these athletes all the way up to, with some of them, international adult and masters level lifting. It’s a full life of development done by the same coach and the same club.

So actually, the first year of training for most of these kids is just general physical preparedness training, moving around, getting to know your body, and doing generally physical things that do not involve weights and barbells and the other 10% simply involve broomsticks more or less to start to develop a good technical practice before there is any load applied. And then in the second year of training the ratio goes from 90% / 10% from general physical to special preparedness to actually using some technique with some weights to moving it to 80/20 or something like that. So it’s during this period of development hat coaches are able to really instill good technical practices in their youth because as you well know, youth take much better instruction to technical practice and last much longer than already well-formed adults.

So basically technique is always a focus of training from the very early days all the way to international lifting. It’s always technique, technique, technique. It’s always a priority, it’s never dumped, and it’s something that always stays with that coach and with that athlete.

So because of this, there’s this illusion that you see an athlete do something with super great technique and you think “Man it looks like he doesn’t even try, maybe I could pull just like that. It doesn’t seem like a challenging weight.” but this is not really the case. It is precisely that good technique that allows him to lift that weight with what looks like relative ease. What can an athlete do with that least amount of input energy for the most result of weight on the bar? So if the lift looks the easiest and there’s the most weight on the bar, that’s how you know your technique is really good.

What would you recommend to develop technique for an already experienced lifter?

Summary:

- When Sheiko receives a new athlete that is an intermediate, he keeps weights around 70% and looks for strength imbalances between legs, back, pressing muscles, etc. in order to program the correct movements.

- A coach should program general preparatory movements around the weaknesses of the athlete for the best result.

- A coach must be patient. Impatient coaches often use gear, which hurts the athlete’s performance in the long run in Sheiko’s opinion.

When I first get an athlete that is an intermediate that comes to me new, for the list little while I only program 70% or 75% of 1RM to keep it nice and light. Any notes, how the technique looks when they’re doing this lighter lifting, I look at symmetries. Not so much left/right symmetries, but are their legs stronger, is their back weaker, is their pull stronger, is their bench weaker, etc.? So the job of the coach is to detect the errors of the technique or the weaknesses of the lifter, to pick the right special preparatory exercises to make sure to fix those weaknesses in the best way possible.

So these exercises can be ones that hypertrophy or strengthen the muscles generally, for example the biceps, triceps, pecs, shoulders, or they can be exercises that improve flexibility or exercises that improve endurance, for example. Whatever the athlete needs.

So if I see an athlete not being able to hit IPF depth, special exercises I would do for that would be a 2 second, then the bottom pause squat where the athlete pauses half way down, pauses for 2 seconds, and then dips into the hole super quick after that. And what’s pretty much known to everyone is the box squat, where you hit a box at parallel and then you slowly lower the box over time to make sure the athlete gets comfortable squatting low. A really good side benefit for beginners and intermediates, when you do a lot of this 4 or 5 rep exercises with slightly lower weight in the special preparatory movements what you get is a really good increase in hypertrophy which is also beneficial . Basically don’t be fooled by the process of when an athlete starts to exhibit technical perfection at these lighter weights due to this inclusion of special preparatory exercises. What you eventually have to do is test these athletes at 80% and 90% and close to maximal weights and if the athlete still breaks down then when they can’t consciously think about these weights anymore, it goes back to automation. If the automation is still a bad technique that means that the retraining hasn’t worked sufficiently yet and the athlete needs to go back to technical alteration training.

The most quintessential element of being a good coach is patience. One of the way that a lack of patience exhibits itself with younger coaches is they can’t wait to put in the time with athletes to build basics so they often times unfortunately turn to banned substances in the IPF, perhaps to sort of erase that patience and get to that other road quicker. One thing they forget about is that anabolics help the muscle grow much faster, but they don’t really help the connective tissue grow faster, which leads to a higher rate of traumatic injury. So especially in the context of tests and federations, what you’ll have is a lot of guys will run a lot of gear and initially get a really good result and exceed their levels really quickly, exceed their competitors at their previous level, but because they can’t be on gear all the time, often you will see a regression back to old results. During that time, the other athletes have been training drug free, putting in high quality work, not taking these short cuts, and they will catch up and exceed the athletes that misuse the doping process. A lot of coaches will disagree with me about these thoughts so I would really like to underline that these are my personal thoughts.

How long would it take for an ‘inherited’ athlete to gain technical excellence?

Summary:

- With a newly inherited athlete, technique is the top priority until it is consistently good. This can take anywhere from 6 months to 2 years.

- Most athletes lose patience, have good form up to 90%, but revert to bad technique at higher loads.

It could be 6 months, one year, or two years of real technical intensive work where you number one priority is changing technique and not exactly pushing high loads. Basically in athletes in which the error is very egregious and obvious, a lot of times it’s an automated error like “that’s just how they squat now.” Even when they stop thinking, it goes back to that. So the first thing we have to do is break that habit and then you have to rebuild anew and that can take a really long time.

A lot of athletes don’t have the patience to go through this entire process. Some people get to where they’re great with 90% loads or so but then they get to the competition, they are under a lot of stress and they think “I gotta stop worrying about technique. All I have to do is sit down and stand up with as much weight as possible.” and that’s when you see technical breakdowns in a lot of people.

Not all athletes have the wherewithal or the patience to practice technique for months at a time, really bang it out to make sure they fix what they need to fix. A lot of athletes will just verbally say “I give up, looks like my technique is not gonna change, fuck this, I’m gonna go up to my old ways and that’s good enough for me.” Where that leads is that you never quite see the kind of numbers they could be lifting had they fixed their technique.

What are the general rules for technique on the big 3?

Summary:

- Squat: keep the weight over the midfoot.

- Deadlift: some athletes rush the lockout in an attempt to develop speed, but speed starts at the bottom of the lift.

- Do not look too far down during the squat or deadlift, as the rest of the body follows the head and this can create a loss of balance.

- Bench: bouncing the bar and not arching are the two most common errors.

Number one rule for squatting is that no matter what kind of build you are or anything the barbell or a service the athletes’ net center of gravity, athlete plus barbell, has to be over the mid-foot. If the center of gravity is too far forward, you risk either falling or stepping forward during the ascent of the lift. If you sit too far back you get a rounding of the lower back and then a dumping backwards or falling backwards and that’s potentially a bad idea.

An interesting technical quirk I’ve seen in over 35 seminars around the world, with the deadlift, in Israel and England, people seem to pull with a decent velocity up to where they get past their knees and they get into their hips and they snap the bar back really fast and tilt their head back really far.

I ask “Why are you rushing the end of the lift?”

They say “For speed development.”

Speed starts at the bottom of the lift. With 300 kilos on the bar, you’re not going to be able to do that with 300 kilos. If you really want to focus on speed you have to focus on starting at the bottom instead of snapping at the top.

Another big technical error I’ve seen on the squat and the deadlift is that people look down, even at the beginning of the lift. This is a bad idea because the neck follows the head and the rest of the upper body follows the neck and you have more of a chance of leaning too far forward when you’re looking like that, which of course takes the center of gravity away from the mid-foot and disrupts the lift so there’s more of a chance with more, like, rounded or tilted forward upper body, there is more of a chance of missing depth on the squat and there’s more of a chance of falling forward with the weight even if you do hit depth and come up

Of the 12 countries where I’ve given seminars, 97% of the athletes pull conventional. When I ask them to try sumo, they say “we just started conventional and that’s what we’re taught and that’s what we do.”

A lot of people I’ve introduced to sumo right then at the seminars. When they widen their feet and try pulling sumo they say “wow this actually way more comfortable for me than conventional.”

The big technical area I see in benching is bouncing the bar off the chest, which is illegal in every powerlifting federation. Another quirk is about 75% of the athletes for some reason, even if they have really long arms, will take a closer grip on the bar instead of doing maximum legal width. They really have not taken account the fact that there are two factors that make maximum legal width a good idea. One is the total amplitude of barbell motion is lower so it’s less total work that you have to do and second of all it involves your pectorals muscles more which are really strong and can press more weight than you can with your triceps.

A lot of athletes, even in the lighter weight classes, for some reason just don’t know how to arch. You’ll see a 60 kg girl just very thin will pull the same kind of arch as a 120 kg males, basically just laying there like a log. To me that’s an instant giveaway that the majority of athletes are not training with coaches, because if they were these are very easily solved problems.

What are some general programming rules you follow for the squat?

Summary:

- You must ease a new athlete into the Sheiko system, you cannot jump right in.

- The athlete’s ability to recover is very important.

- Sheiko starts with 2x weekly squatting, observes the ability to recover, and then adds a third squat exercise if the athlete is handling 2x weekly well.

- If that goes well, an athlete will have a “stress test” set of squats added to stimulate supercompensation.

- When using percentages, the base 1RM should be realistic, not hopeful.

The first thing is whenever you take new athletes that haven’t been used to my system, you can’t just get right into my system that I use for advanced athletes. You can’t just get right into it, you have to ease them in.

A ton of this is going to be dependent on the athlete’s ability to recover, so the first step I usually take is just twice a week frequency for squats. So, squats Monday and Friday, something like that. You exercise twice a week. So what I’ll do after that is if they’re recovering very well and it look they’re recovering just fine with a lot more in the tank I’ll keep the frequency the same but I’ll add an extra day of squats. For example, Monday they would squat heavy, then they would bench relatively heavy, then would squat after that for some more volume. So there might be two sets at 80% or 85% and 4 or 5 reps per et on the firs squat exercise, but on the second exercise it’ll usually be with a lighter load but more volume, like maybe 70% at 5×5.

So if the athlete is able to survive the kind of program I just described pretty well, then every couple of weeks we offer the athlete an opportunity what I call a “stress test” set of squats. So for example, I’d do 2 sets at 50-60% for 5, after than 70% for 5 sets for a different of reps each set. First 3 reps, then 8 reps, 2 reps, 9 reps, and so on. Another kind of pyramid is 3, 5, 7, 9 and there is also 8,6,4.. . down back the other way.

There are two basic methods that we use for pyramids.There is the stagger method, which is basically 2, 5, 2, 8, 2, 9 and then there’s the other one where you go up in reps and back down in reps evenly. There’s a lot of variation with this stuff and this is published in my book. I tell this in a lot of my seminars. This type of super stressful set or special set are usually only able to be handled after every 2 weeks or so and only during the base building period of the training, not the peaking, because the muscles need a very long period to recover. So 4 weeks before competition we don’t do any of this kind of work.

And so I’ll include these pyramids in the bench press as well every now and again. It’s like an overload, a super compensatory shock to the system that requires several weeks to come out and then we’ll shock the systems again, several weeks to come out of it, and then when they approach competition period, we take that away for the taper.

The rule here is that the higher the volumes, the lower the intensities you have to put on the bar. You’re not gonna do 90% for 6 or 7 or 8 reps. If you’re shooting for super high intensities you gotta make sure you’re bringing the volumess down because you’re not gonna be able to do do 90%+ for more than one or two reps at a time, not a whole lot of reps. So I’m actually very excited that for Americans to try these programs that they system we’re working on together and I can’t wait for the Americans to taste the horrors of these programs for themselves. But the athletes that can, have the willpower and the ability to recover to actually complete these programs, I guarantee you that they will be able to increase their strength.

I say this to a lot of my Russian atheletes: A huge mistake people make in programming is when they base their percentage numbers off of “hopeful percentages” versus realistic percentages and it’s a huge mistake people make everywhere.

For example, an athlete’s currently squatting 200 kg and he says “Alright, I have a meet in 8 weeks. I want to squat 220 kg.” and he starts programming off of the 220 kg number. And so he squats triples at 80% or doubles at 85%, for him that’s actually like 90% or 95% so what ends up happening is that volumes of repetitions at that relative intensity is already enough to cause an overwhelming of recovery systems. So these people write on the Internet when they misuse the program and put these fantasy numbers in “oh I could recover. This program sucks. The Sheiko program sucks.” And if I lose my temper I say “It’s not my program that sucks, it’s the shit in your head that sucks.”

How should you train the squat, bench and deadlift differently?

Summary:

- Because the squat and deadlift use larger muscles and use many of the same muscles, recovery needs to and training volume, when compared to bench press, need to reflect this.

- Squatting twice in one session with bench press in between provides additional recovery.

- Assistance work is critical for address weak points on the competition lifts.

- Close variations to competition lifts (e.g. deficit deadlifts) can help achieve necessary volume while allowing more recovery for the athlete.

As the squat and deadlift are powered by very large muscles of the legs and back, whereas the bench press is powered by smaller upper body muscles, biceps, triceps, all the heads, the deltoids, the pecs, what ends up happening is the larger muscles take a really big recovery demand.

One way in which I factor this into my programs is by programming them less frequently or less voluminously or less intensely. For example, if I’m attempting to squat plenty during one session, I’ll squat and then program in a bench press pushing exercise in between and then squat again so that you can recover a little bit to be more productive and effective in the second squat exercise. So even though the characteristics of the first and second squatting exercise, which is like the Monday example we discussed earlier, even though those examples are different – you’ll still get better performance because if you squish a bench press between the two squats, then you get a little bit of recovery from squat one to squat two and you can do a much average level of intensity. And over the long term, about a week’s worth of recovery, if you do back to back exercises if you split them up, like upper/lower upper/lower within a single day that you get better recovery by splitting things up vs. doing them back to back. So I’m very much opposed to the programming that other individuals will do where they do squat, bench, and deadlift every training day, say Monday, Wednesday, Friday.

There are two distinct problems with this approach: one, because squat and deadlift both use the lower body musculature and you’re doing them with the same frequency as the bench press, you’re getting something like 3 times more volume load for lower body and back musculature as you do upper body musculature, which is completely backwards, right? You’re training the muscles that can recover the least, the most. That’s problem #1.

Problem #2 is that if you’re only training the squat, bench, and deadlift every single day with no assistance work, how are you supposed to use special prepatory exercises to fix technical flaws, etc. when you don’t allow for this and you only ever do the competition movements? I am categorically opposed to that kind of training. So basically, there is some form of pressing almost every single session that I program, so 3 to 4 pressing session a week, but for squatting and deadlifting, an average of 2 squatting and/or deadlifting exercises per week, so it ends up being 4 of each. The squat and the deadlift have to be treated as intersecting muslce groups, thus they cannot be as overloaded in a vacuum by themselves. They cannot be treated as separately fatiguing effects, you must make sure that you realize there’s a big interfence effect there and reduce their overall volumes. Some people who criticize my porgramming say that I program deadlifts too frequently because I program deadlifts roughly twice a week. They will maintain that deadlifts should only be trained once every 7 days, sometimes every 10 days. So when individuals come ot me with this kind of protest that I’m doing deadlifts too frequently and they say it’s better to do it every 7 or 10 days. I say “yeah, sure, because of the huge recovery demand that’s why you’re doing that, but what about the technical demands of the deadlift? How are you supposed to improve your technique if you really only practice it 3 or 4 times a month? This is not enough from a technical perspective to achieve the prowess we want with deadlifting.

I’m the first international caliber coach that offered that two different approaches to squatting or deadlifting or bench pressing be taken two different exercises to work on them be taken in the same session. For example, a deadlift could be done from a deficit to work on breaking off the floor and then after that another deadlift exercise later in that session later could be done, for example. I was the first individual to offer that up as a viable way of training. At first this kind of approach, doubling up on lift variations in the same session was seen as antithema and a really bad idea by most, and then eventually because of successes and people had adopted the methodology and saw that it worked, it’s now becoming more popular.

One other example, taking a page from Abiga’s book – the big difference between his philosophy and the philosophy of the USSR and other weightlifting countries was he said “If circus strongmen can do warm ups and training in the morning and then every night they can perform in the circus and basically go to limit feats, why can’t weightlifters do the same thing?” He had experimented going all the way to 3 to 6 training sessions in a single day with his lifters. One of his programs, he had lifters do 6 training sessions Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and 4 training sessions Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday. Every training session was 45 to 60 minutes long and in each one of these sessions it was either the snatch or clean and jerk and they would work up to a max in every single one of these periods. And even, granted, that that’s the case – we still have debates: is it possible to translate Balgis Bulgarian weightlifting system into powerlifting application? The big thing people are forgetting when they try to apply the Bulgarian system to powerlifting is the huge difference in circumstances. It’s a difference between atheltes and indivudals that have jobs or have to go to schools. The Bulgarian system had exceptional medical staff and care. They had an exceptional pharmacology. They had massage specialists giving massages after every training session. They had a dietian, lived in a training camp, did work, and only lifted weights. Even still, the majority of lifters did not survive the system. Some combination of pure overtraining or traumatic injury would occur. Most left, only a handful of athletes survived this system and they had the best prepatory methods. These were the best of the best, the elite, they were already well prepared with high volume training before then and they still didn’t survive.

All that aside, that we don’t have the resources for most of our atheletes to replicate the Bulgarian structure, recovery, etc., we need to close this debate on “Is Bulgarian system applicable to powerlifting?” once and for all. The answer is no.

Another thing people forget when trying to apply the Bulgarian system to powerlifting is the snatch and clean and jerk take some fraction of a second, while a squat, bench, and deadlift take multiple seconds, thus multiplying the amount of static and dynamic stress on the body for the power lifts. This exposure primarily tisaxial loading through the spine increases the chance of spinal fracture, compression, and bulged discs, so when I moved from Kazakhstan to Russia in 1997, I came to a commercial powerlifting club that was basically designed only to accommodate elite lifters and for these people, they were financed completely, the powerlifters that stayed there, they were fed all of their meals at the cafeteria and they had excellent recovery resources. I was able to take the number of training sessions up to 8 training sessions total.

What do you feel are some things falsely associated with the Sheiko methodology?

Summary:

- There have been many misunderstanding, primarily stemming from Sheiko program spreadsheets circulating around the Internet that were written for a specific athlete, not whoever is downloading and using the program.

- Certain older programs for equipped lifting were written for older less effective equipment, not the effective equipment used today.

- It is important to be patient. Never rush development and always do no harm.

- Technique is essential and is a direct reflection of the coach.

- Programs must be individualized. Variations in nutrition, love life, etc., make a big difference.

- Supercompensation is necessary for the best competition result.

Yes, there are misunderstandings, but what’s even worse is when people basically talk smack about the program, saying it’s not survivable, it’s a stupid program, it’ll get you hurt and the only way to survive the program is to be on lots of drugs – even though I have plenty of drug free lifters that do very well on the program.

So when we talked a couple months ago, you said “There’s a ton of popularity for your programs, Boris, but it’s not clear how to execute them or if they’re true to the spirit of your name = maybe you’ll come down here and sort this out.”

I say “How about I come down and write some new programs right in front of you, we tell them to the world, and there will be no doubt that they’re from me. We can finally abandon all of these old programs and discussions about whether people are doing them correctly.

One of the programs that I’ve seen a lot was a beginner program to establish bench press priority for a female lifter that I trained when she was 15 years old back in 2002, so it’s a mildly outdated program that won’t work for her nowadays, so maybe it’s time to establish some new programs with my principles.

So basically there are a lot of technologies I’m using in my programs now where it it was designed for equipment that wasn’t as good back then, like single ply IPF. Now my programs for single ply IPF guys have more band, chain, dynamic effort type of stuff, better assistance that work better for more effective powerlifting equipment. Back in the day it was for really crappy equipment or raw lifters – not a lot of new technologies.

The first principle, like in medicine, is do no harm. I want people to understand that patience is the quintessential virtue of a powerlifter and a coach. If you plant potatoes and expect a harvest in two weeks you’re running a fool’s errand. Growing potatoes you’re going to wait a certain amount of time after planting, then you’ll have potatoes. The same thing applies to an athlete: be logical, take all the time you need, don’t rush athletic development.

The second principle of training that I have to attest to in importance is that of the supremacy of technique. Technique, technique, technique is absolutely essential to building up the biggest result possible.

Every time an athlete is representing their coach at a competition it is the technique that is a direct reflection of the coach, so even if an athlete achieves a big result and pulls a lot of weight, if they look like a hook or something while doing it then what the hell was the coach doing? Was he playing checkers or chess the entire while their lifters were lifting? What the hell is going on? It’s a direct reflection of the coach.

The third principle is one of individualizing the program to the athlete’s particular circumstances in the moment. For example, is the athlete having good nutrition or bad nutrition? How is the athlete’s love life? Is it stochastic or not? If you know a lot about the athlete’s individual circumstances in the moment you can alter the plan intelligently to get the best possible result. Like I said in Russia: “Small children, small problems. Large children, large problems.” With very young child lifters the only real problem is the parents will come and complain and say they told their child to do something but their child says their coach told them to do something else. So I need to sit them down and say “Listen, you coach is a very important person, but your parents’ word is still law. You still have to listen to them.” With adults, intermediates and advanced lifters, as a coach you become a consultant on their financial lives, how to make sure they get work and are productively employed, how to make sure their personal life is going okay. You become a consultant in all things to help your athletes in any way that you can.

My wife often complains that I get more interactive into the lives of my athletes than I do my own children! You have to take the individual variation into account. For example, if an athlete fails a class or does poorly on an exam, they will come in defeated already, the weights will seem harder than they should be, so I reduce the weights a little bit to accommodate. On the other hand, if an athlete just kissed a certain girl for the first time, he could come in and it’s 80% on the bar, but the weights are flying up so you might increase the weight just to accommodate to that super normal amount of strength.

Another principle I like to bring attention to is that of super compensation. We’re very careful to make sure we bring in our athletes very well rested and recovered for the tapering period. We want them to literally try to pull into battle, they’re ready to wage war because they’re so reduced in their fatigue.

In powerlifting what we try to do is we bring them to their pre-taper peak maybe 17 days out or so on average to allow for plenty of recovery to occur. In weightlifting circles sometimes it’s 9 or 10 days before the competition.

What often happens in powerlifting without good coaching is that individuals have confidence issues regarding whether they are as strong as they think they are and are they on track? They’ll do 90%+ weights, sometimes every session or every other session – just way too often and way too soon before competition. They’ll arrive at competition tattered, worn down psychologically and physiologically and be unable to perform at their best. Sometimes if we’re testing or going to close to limits (95% or so), if the athlete doesn’t seem confident they’ll hit the weight, I’ll stop everything at the gym, whether it’s 20 or 30 people, and bring them over to get behind the athlete. Everyone starts clapping, there’s a lot of attention, they get the weight, and that helps move the training process along.

Sometimes I’ll walk over when they’re lifting and they’ll say to me “hey, just because you were close by, it was easier for me to lift the weight.”

What percentages are generally used outside of a peaking phase?

Summary:

- General prep: as few 90%+ lifts as possible, with a test at the end of the block to gauge progress.

- Competition prep: generally will test at 100%, 103%, 105% 17 days out of competition. This would differ for an elite athlete.

- This can differ for each lift too. Weaker lifts need to be tested more.

In general preparatory period, we try to do as few 90%+ lifts as we can, so for a general prep phase I won’t program any 90%+ lifts – it will be 80% or 85% on average. Sometimes at the end of general prep we’ll do a test getting people to do a simulated meet, having them go to true maximums, and then we’ll reconfigure the next period based on those updated numbers, if they’re improved, regressed, or whatever. And then during competition phases we only go to a true max one time outside of the meet itself, about 17 days before competition where we’ll take someone to 100% to do their pre-competition test. We base their competition numbers on that, but other than that we go to 90%= very rarely.

That 17 day pre-competition test, for beginners and intermediates we go to 100% of their predicted max and if they nail that we go to 103%, 105% to really test the waters because we won’t know these lifters as well yet.

For advanced or elite lifters, we only to to 90% or 95%, basically to their planned first attempts for their upcoming meet 17 days later. They hit their first attempts and based on how that attempt looks to myself and them, we already know that their technical and psychological stability is good, so that we can project from there an later meet numbers without having to go to an actual max 17 days out.

But as you and I both know, super elite athletes that are incredibly strong at all three movements, such as Eddy Coan, there are very few of those people so it’s much more common that an athlete has two strong lifts and one that lags behind. In that case 17 days out for the lift that individual we’ll go 90% or 95% to get a test of things because these are predictable, good lifts. For the weaker lift, we’ll go to 100% or 103% or 105% to really test the waters because we never quite know with that lift and we have to reexplore it.

As an example, for Ravel Kazakh one of my famous champions, his benching and squatting were superlative, he was beyond world class. He was squatting and benching above world records all the time, but his deadlift was limited by the fact that had really short hands and fingers and had grip issues on the pull, so when we’d do his 17 day out pre-peak test we’d have him just do 90% or 95% on the squat and bench because we knew those pretty well, but on the deadlift we’d go to 100% to 105% – whatever it took to really get a feel of how that deadlift was behaving.

Is there a time and a place to fail a lift?

Summary:

- Sheiko only calls for attempts that he knows his athletes can hit

- Psychology is very important for an attempt – an athlete must be sure they can hit it

When I have athletes go to limit weights, I only let them do the weights that I know they’re capable of.

For example, if they go to lift a 90% weight and it looks smooth and fast, great, go to 95%. If they go to 95% and if that looks like another 2.5kg is going to break them in half, I cut them off. They’ll say “coach, give me the next attempt, I’ve got this” and I say “no gimme gimme gimme, none of that. There’s no way we’re doing that because we’re setting you up to fail.”

I do not program any lifts I don’t think there’s a high chance of success with. Coming here to film these videos, I have a team I’m coaching back in Russia and I told my athletes and the junior trainer I left in charge as the coach for that meet “look, you don’t take any attempts that you’re not confident in getting.” If the athlete doesn’t think it’s gonna happen, don’t go for the attempt. This applies to competition as well.

In really high levels we say “are we going to risk it to win?” If I have an athlete that is squatting 200 kg but they need to squat 210 kg to win, then the next question is not should I let them squat 210 kg and roll the dice, the question is “well, if I program 205 kg, will that get them a top 3 finish on the squat? Will that set them up much better for their total? Almost always we’ll go for 205 kg to build the total to get the medals but every now and then you have to set people off to that mythical 210 kg, right? The attempt that never was. What I have to do in that situation is really lift up the athlete emotionally, particularly in a patriotic slant. I’ll say “Your last name is Ivanoff. What kind of Ivanoff are you? Are you a real Russian man? Why don’t you show this crowd what a real Russian can do?” And by the time I am done with them, they don’t know what the hell is going on. They just need the bar – that’s all they need.

When you go in for a lift like that you can only think “I’m getting the lift. I’m going to lift it.” If you think maybe I won’t or if you think well maybe I’ll get injured that’s it. It’s over. You have to think one-track mind, it’s gonna happen.

When I used to tour around and recruit for the national Russian teams at regional clubs I would watch individuals max out and guys would take a first attempt at a snatch at 100%, fail it, second attempt, fail it, third attempt, fail it. I would say “listen, I can give you ten attempts if you want but because you missed your first two and it’s over. You’re not gonna recover physically or mentally. There’s a moral degradation that occurs there with enough misses we just gotta shut it down.

Getting hyped up for a lift – what is its role in training and competition?

Summary:

- Psychological arousal is needed for maximum limit tests

- Psychological arousal and physical arousal are linked together, so enormous psychological arousal should be used sparingly to manage athlete recovery

- Using chains or bands or deficits can be a useful trick for stimulating physical recovery with less psychological arousal or effort

At very limit weights, any time you do a test, requires a considerable psychological arousal and that disturbs the nervous system to some extent. The nervous system and psychological recovery are one in the same. They require a much longer duration than physical recovery and has to be worked into a program.

One of the first people to talk about this is Fred Hatfield (Dr. Squat) in the late 80’s wrote a book called “Powerlifting: A Scientific Approach” and he discussed how sometimes it is necessary to do 5×5 at 90% but elsewhere he would say going to limits has to be done sparingly and carefully because it is so hugely taxing to an individual’s ability to recover from future workloads.

Something to consider: Hatfield was the world champion of powerlifting twice, but was never the American powerlifting champion. I wonder why that was the case? (This is a riddle for Omar to consider)

Basically in the prepatory, base building phase, I don’t do any 90%+ lift without psychological arousal, then I do other techniques for sure and I don’t go to maximum or limit weights.

A cool psychological and physiological training tool is lifting with chains where at the top of the lift it’s actually appraising 90% of our 1RM but the reality is at the bottom of the lift it’s more like 70% so while in your mind there’s only 78% on the bar it’s not as psychologically taxing as if we put 90% on the bar, but it’s physiologically in some ways comparatively taxing so you can get a little more physiological oomph by tricking the athlete into not freaking out as much by reducing the bar weight and increasing chain weight.

Another example is you couldn’t get someone to go 70% for just a couple of reps on a deficit deadlift and instead of a like a two or three inch deficit we’re talking maybe a four or five inch deficit if an individual hits a certain number of reps at 70% of their deadlift with that kind of huge deficit then I know that athlete is ready for a new PR – their deadlift has gone up without actually having to test the deadlift itself and expend a lot of psychological effort to do so. I can trick the bodies into working at 80% or 90% or more relatively intensities for the athletes with deficit pulling, squatting with chains, but keep the psychology of the athlete from being affected by the imposition and fear of such loads. This allows for a high level of adaptation but a lower level of total fatigue.

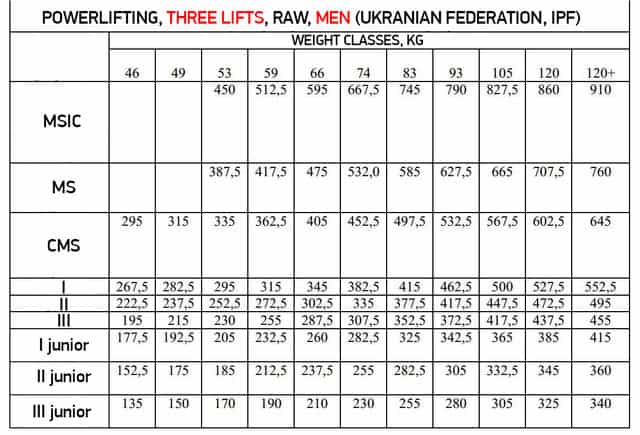

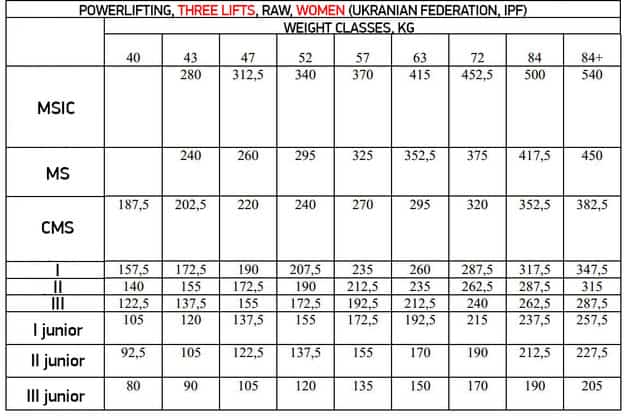

What defines a novice/intermediate/advanced lifter?

Summary:

- See chart below for actual powerlifting classifications (raw and equipped)

- Beginners and intermediates train 3x weekly, MSC train 4x weekly, and elite lifters train 4x weekly, with occasional use of 5x weekly training sessions in specific prep phases

- Load variation is important to achieve different training effects

- Heavy loads: drive adaptations

- Medium loads: reaffirm strength gains

- Light loads: active recovery

- The average load of Sheiko athletes is in the 71% +/- 2.5% range, across all classification levels

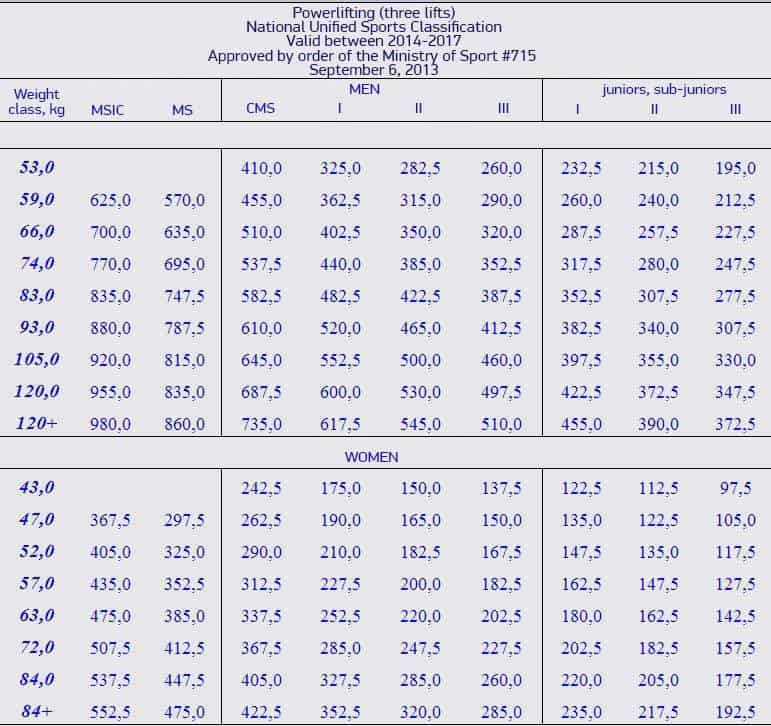

Russian classification for equipped lifters (source):

Ukrainian classification for raw lifters (source):

In Russian weightlifting and powerlifting thinking there are more classes than that. There is the novice/beginner, the student trainer class, the sub master candidate for master of sport, then actual master of sport, which means like prime of competition, and then not anymore advancement in training age but advancement of ability is called international caliber master of sport, which is when you’re eligible for selection to the Russian national team for example so those are the different classes of athlete.

So it’s all based on your total or Wilkes formula. If you’re totaling a certain amount in a certain weight class, you’re a novice or intermediate or advanced – it’s all about how strong you are. One of the things that is determined by how strong you are is how often you train per week.

Beginners and intermediates usually train three times per week, master of sport class sort of advanced athletes would train maybe four time per week, whereas international master of sport would train four times a week but sometimes during certain periods where they’re not working as much when they’re preparing hard, they’ll train five times per week given the proper recovery resources.

So basically as you go through these levels, an average training session is 60 to 90 minutes and something like 90% of that training session will be occupied with general physical preparedness for beginner athletes. I’ll have them do exercises with a broomstick and then go play soccer or basketball, whatever is in season, just move around and run. The Soviet system has something called light athletics which is like track & field. Heavy athletics is where you throw stuff or pick up heavy weights. Eventually you see an even transition throughout that development where at the end, international class lifters will do 90% of their session work with actual specific heavy weights and only 10% of it will be warm ups and plyos and stuff lke that, which is considered general prep.

In Russia there are about 12,000 sport schools and they all train under one developmental system and they produce a line of athletes that eventually culminate in national team champions. This is not just for powerlifting or weightlifting, this is all forms of sport. There are some schools that are sport-specific, like just track & field or just soccer, but others teach many sports. These schools have various developmental levels of athletes and you can tell how many coaches there are running the same programs, evolving their own athletes and eventually these athletes evolve into advanced competitors under one developmental system and even if they go to other clubs it’s the same basic system so they can continue to receive the appropriate development.

[Note: Boris recalls another training principle from an earlier question that he’d like to share.]

A critical principle is load variation. Instead of going hard all the time, what we do is we combine an integration of heavy, medium, and light loads. For example, we’ll do a heavy load in volume, heavy load in intensity, a medium load, and then a light load. The medium loads essentially reaffirm gains, light loads allow for a form of active recovery where your muscles recover but are conserved in their abilities while they recover. The heavy loads primarily drive the adaptations the light loads allow for recovery, and the intermediate loads allow for a reaffirmation of that progress. By balancing those we can continue to elevate the athlete further, continue to provide enough variation so that the adaptation does not become stale, and by varying things allow for the athlete to reach up and up and up without accumulating too much fatigue to interfere with them.

It’s actually featured in this book that I just gave you, Omar, and this kind of colume load variation occurs at the microcycle level for example some of the days of the week will hard, some moderate, some light. This also is a feature of mesocyle plan. For examle, we might have one hard week, a moderate week, another hard week, and then a light week or something like that. The number of mesocycle variations that I have described in the book, which is as many as 12 distinct loading paradigms throughout a mesocycle to optimize performance relative to the situations deamand so baically we keep track of all the heavy light and medium workouts of all of our athletes, especially our very good ones. What that allows us to do is we look at average tonnage and if their average tonnage is going up, we can tell that they are improving and of course the fatigue is stable. They’re improving in their abilities even though we’re not going to max them all the time, so the average tonnage matters even if you’re not going hard all the time if you measure and track everything you could be that much better at planning a mesocyle.

I conducted a statistical analysis over the 7 years I was the head of the Russian national powerlifting team of the top nine athletes that I’ve ever coached there and a pooled statistical analysis that the average, this is important, the average load per all training session was 71% +/- 2.5% either way. That was the average load used to answer one of your earlier questions.

If the athletes train at an average in the mid-60% range they’re going to start to get minimum improvement or no improvement on the other if they train in the 80% to 85% range, then they are going to start overreaching within two weeks of that at the volumes I prescribe, which is what that low 70% number is the best middle ground i’ve found.

After a week of training I’ll do analysis on some of my athletes where I calculate their entire average intensity and if there are alterations, like if a guy isn’t feeling good I won’t push them as hard, but if they’re feeling great I’ll push them even harder. I’ll look at all the numbers and if he’s doing 68% on average in the deadlift over the last couple of weeks, but 73% on the squat, I will lower the squat average intensity over the last couple of weeks or in the next week and raise the deadlift because the deadlift has been under trained while the squat has been a little bit over trained during that time so basically sometimes weight lifters will ask “How come powerlifters have this average intesnity of 71% and weightlifters have an average intensity of 77%?” Well, in powerlifting you base your squat and your deadlift off of your competition best squat and deadlift, but if you’re talking about the number you’d base your weighlifting movements. Your pulls, like snatch pulls, you base off of your snatch, so you’ll have snatch pulls which are 120%, 130%, which is why their average intensity is higher at 77%.

A lot of times there’s a relationship between the clean and jerk and the squat so you base your squats on your jerks and you know your squat, if Klokov or something you squat 300 kg and jerk like 290 kg then of course there’s gonna be a situation where your squat is over 100% of your jerk, which is how come those numbers get dragged up to 77%.

The relative percentage there is based on a different number and because the weightlifing movements are fundamentally less disruptive and less heavy than the powerlifting movements they can tolerate a higher percentage.

What are you thoughts on overtraining?

Summary:

- Sheiko thinks overtraining is nonsense

Because in large measure I don’t want to fill my head with such idiocy, but I’d like to see that an individual who has such ideas on the platform at European champions or Worlds to see if he could show us how it’s done. Any theory needs to be supported by the actual package. A lot of people theorize, not a lot of people put stuff into practice. Sometimes you’ll read a program and you just think the person that wrote it like… have you tried this yourself? I mean what the hell is this?

There are bunch of “coaches” in Russia now just get above the masters class stuff so basically like what will be considered raw elite here. They get their first couple big meets under their belt and immediately say on the Internet that they’re taking client and they’re a coach and this is no good. It’s not worth thinking about though, as you cannot make it illegal; it’s the Internet. I worry about how many people that person is essentially maiming with their stupid training practices.There are very few athletes that become great coaches. Plukfelder from Russia, a weightlifting coach, and Abadjiev are exceptions to this. Abadjiev took 3rd at World’s at one point and he said the big flaw these people run into is they tell their athletes to do as they did and the student will also be great, forgetting the importance of individual differences. What worked for them may not work exactly the same way for the athlete they are coaching.

What do you think of autoregulation (RPE)?

Summary:

- Auto regulation has a lot of validity for athletes training for fun or just to get stronger

- Athletes that want to compete at the highest level should have a coach

- An athlete using auto regulation is often tempted to err on the easy side too often. To set a record, what has to get done has to get done.

Auto regulation is a bit of a fad so to speak and fads come and go. It’s a system that has a lot of validity for individuals that are training just for fun. If you are training as a serious competitor how you feel doesn’t have as much relevance with how you’re actually performing. Because auto regulation is an individual’s choice whether or not to proceed, this somewhat reflects the physiological state but not completely. Thus it is a fine method for individuals who just want to get strong on their own time but for high level competitive athletes there needs to be a coach. There needs to be some accountability. It cannot be feel or auto regulation by itself.

So basically the big flaw with auto regulation is that it’s really hard to tell if you just don’t feel like doing something versus if you actually physiologically are under recovered. So that kind of flaw is okay in a program for someone that just wants to get strong, but for someone that wants to chase records, what has to get done has to get done. The only way you can pull an athlete back if they are under recovered is with the expert guidance of a coach. An athlete by themselves is too highly tempted to just err on the easy side too often.

Closing Comments from Boris Sheiko

Any time you have an interview there’s no way I can sum up 40 years of my professional practice into one interview no matter how long it is. I was giving a seminar and I got super tired at one point and they could tell that I was tired. They said maybe it’s time to cut it off, maybe it’s too much. And I said , yes I am tired, but it’s so awesome that you guys are so curious about powerlifting and my knowledge and my experience that I’m just so pleased to answer these questions. I could do it forever. I could talk about powerlifting for 24 hours straight and I’m just so thankful to get the opportunity to talk about it and I just hope all the lifters in American and everywhere else watching this will take what I said with understanding and hopefully something that I said will help them in their own personal pursuit of strength.